- Organism Chain

- Microbe Chain

- Microbe Food Chain

- Bacteria Chain Of Infection

- Bacteria Chains

- Microbe Chain

Jump to:

What is the microbiome?

How microbiota benefit the body

The role of probiotics

Can diet affect one’s microbiota?

Future areas of research

What is the microbiome?

Picture a bustling city on a weekday morning, the sidewalks flooded with people rushing to get to work or to appointments. Now imagine this at a microscopic level and you have an idea of what the microbiome looks like inside our bodies, consisting of trillions of microorganisms (also called microbiota or microbes) of thousands of different species. [1] These include not only bacteria but fungi, parasites, and viruses. In a healthy person, these “bugs” coexist peacefully, with the largest numbers found in the small and large intestines but also throughout the body. The microbiome is even labeled a supporting organ because it plays so many key roles in promoting the smooth daily operations of the human body.

Each person has an entirely unique network of microbiota that is originally determined by one’s DNA. A person is first exposed to microorganisms as an infant, during delivery in the birth canal and through the mother’s breast milk. [1] Exactly which microorganisms the infant is exposed to depends solely on the species found in the mother. Later on, environmental exposures and diet can change one’s microbiome to be either beneficial to health or place one at greater risk for disease.

The microbiome consists of microbes that are both helpful and potentially harmful. Most are symbiotic (where both the human body and microbiota benefit) and some, in smaller numbers, are pathogenic (promoting disease). In a healthy body, pathogenic and symbiotic microbiota coexist without problems. But if there is a disturbance in that balance—brought on by infectious illnesses, certain diets, or the prolonged use of antibiotics or other bacteria-destroying medications—dysbiosis occurs, stopping these normal interactions. As a result, the body may become more susceptible to disease.

How microbiota benefit the body

Microbiota stimulate the immune system, break down potentially toxic food compounds, and synthesize certain vitamins and amino acids, [2] including the B vitamins and vitamin K. For example, the key enzymes needed to form vitamin B12 are only found in bacteria, not in plants and animals. [3]

Sugars like table sugar and lactose (milk sugar) are quickly absorbed in the upper part of the small intestine, but more complex carbohydrates like starches and fibers are not as easily digested and may travel lower to the large intestine. There, the microbiota help to break down these compounds with their digestive enzymes. The fermentation of indigestible fibers causes the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFA) that can be used by the body as a nutrient source but also play an important role in muscle function and possibly the prevention of chronic diseases, including certain cancers and bowel disorders. Clinical studies have shown that SCFA may be useful in the treatment of ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. [2]

Simply choose from our growing collection of Microbes Keychains. Perfect for car keys, house keys or hiding keys in the flower pot (shhhh), we have many expressive designs to pick from. You'll always find the perfect key ring at CafePress, whether you want an oval-shaped key ring, square-shaped key ring, heart-shaped key ring or rectangle. Uploaded Use the arrow keys or WASD to control the microbe. Try to keep it inside the circle. The chain behind you slowly grows, making you. Try to keep your microbe chain inside the circle while it grows bigger and bigger! Don't get knocked out by the other microbes zooming! Play Count: 10807. Microbes need nutrients for growth and they like to consume the same foods as humans. They can get into our food at any point along the food chain from ‘plough to plate’. Therefore great care must be taken at every stage of food production to ensure that harmful microbes are not allowed to survive and multiply.

The microbiota of a healthy person will also provide protection from pathogenic organisms that enter the body such as through drinking or eating contaminated water or food.

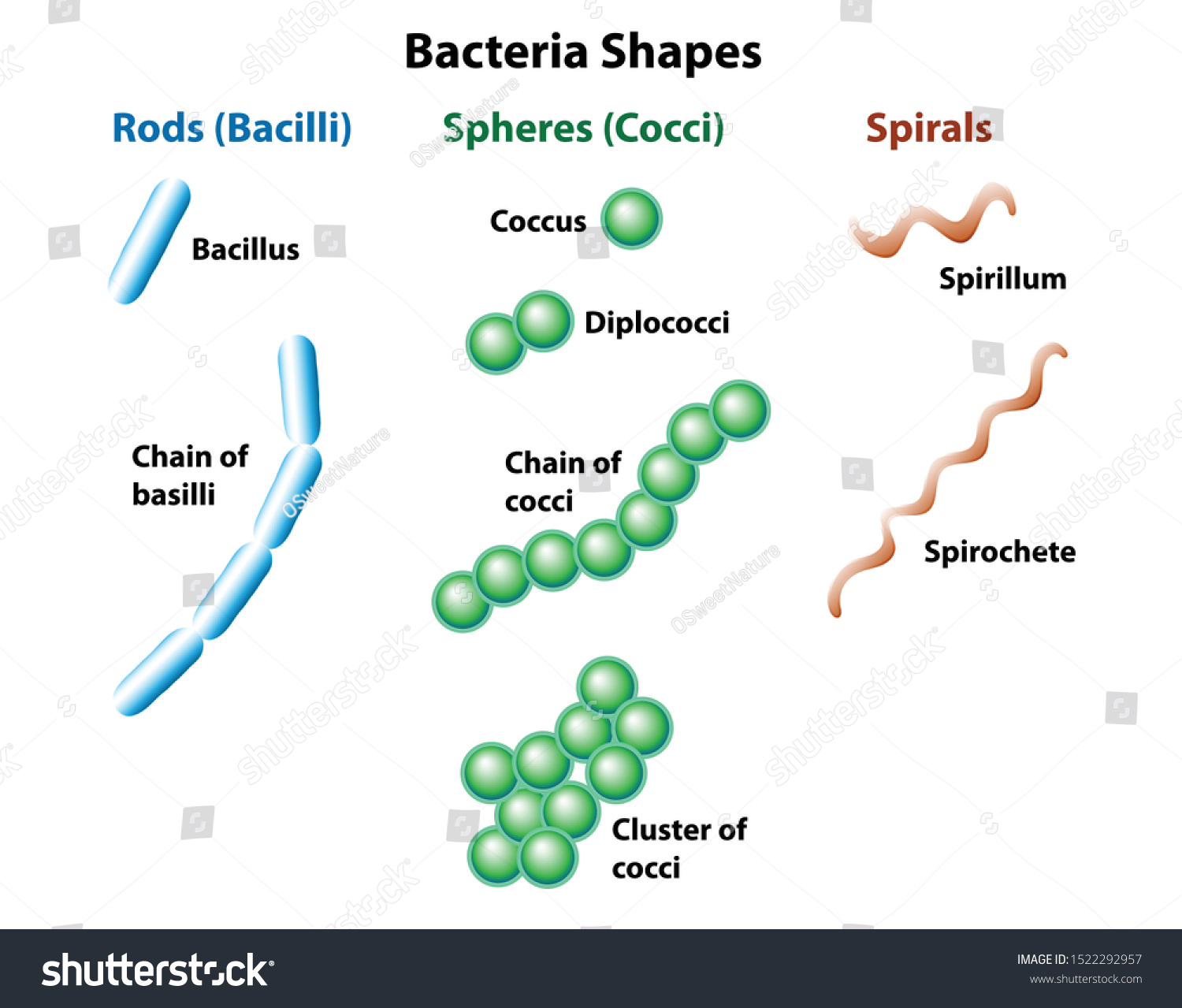

Large families of bacteria found in the human gut include Prevotella, Ruminococcus, Bacteroides, and Firmicutes. [4] In the colon, a low oxygen environment, you will find the anaerobic bacteria Peptostreptococcus,Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Clostridium. [4] These microbes are believed to prevent the overgrowth of harmful bacteria by competing for nutrients and attachment sites to the mucus membranes of the gut, a major site of immune activity and production of antimicrobial proteins. [5,6]

The role of probiotics

If microbiota are so vital to our health, how can we ensure that we have enough or the right types? You may be familiar with probiotics or perhaps already using them. These are either foods that naturally contain microbiota, or supplement pills that contain live active bacteria—advertised to promote digestive health. Probiotic supplement sales exceeded $35 billion in 2015, with a projected increase to $65 billion by 2024. Whether you believe the health claims or think they are yet another snake oil scam, they make up a multi-billion dollar industry that is evolving in tandem with quickly emerging research.

Dr. Allan Walker, Professor of Nutrition at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School, believes that although published research is conflicting, there are specific situations where probiotic supplements may be helpful. “Probiotics can be most effective at both ends of the age spectrum, because that’s when your microbes aren’t as robust as they normally are,” Walker explains. “You can influence this huge bacterial colonization process more effectively with probiotics during these periods.” He also notes situations of stress to the body where probiotics may be helpful, such as reducing severity of diarrhea after exposure to pathogens, or replenishing normal bacteria in the intestine after a patient uses antibiotics. Still, Walker emphasizes that “these are all circumstances where there’s a disruption of balance within the intestine. If you’re dealing with a healthy adult or older child who isn’t on antibiotics, I don’t think giving a probiotic is going to be that effective in generally helping their health.”

Organism Chain

Because probiotics fall under the category of supplements and not food, they are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S. This means that unless the supplement company voluntarily discloses information on quality, such as carrying the USP (U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention) seal that provides standards for quality and purity, a probiotic pill may not contain the amounts listed on the label or even guarantee that the bacteria are alive and active at the time of use.

Can diet affect one’s microbiota?

In addition to family genes, environment, and medication use, diet plays a large role in determining what kinds of microbiota live in the colon. [2] All of these factors create a unique microbiome from person to person. A high-fiber diet in particular affects the type and amount of microbiota in the intestines. Dietary fiber can only be broken down and fermented by enzymes from microbiota living in the colon. Short chain fatty acids (SCFA) are released as a result of fermentation. This lowers the pH of the colon, which in turn determines the type of microbiota present that would survive in this acidic environment. The lower pH limits the growth of some harmful bacteria like Clostridium difficile. Growing research on SCFA explores their wide-ranging effects on health, including stimulating immune cell activity and maintaining normal blood levels of glucose and cholesterol.

Foods that support increased levels of SCFA are indigestible carbohydrates and fibers such as inulin, resistant starches, gums, pectins, and fructooligosaccharides. These fibers are sometimes called prebiotics because they feed our beneficial microbiota. Although there are supplements containing prebiotic fibers, there are many healthful foods naturally containing prebiotics. The highest amounts are found in raw versions of the following: garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes, dandelion greens, bananas, and seaweed. In general, fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains like wheat, oats, and barley are all good sources of prebiotic fibers.

Be aware that a high intake of prebiotic foods, especially if introduced suddenly, can increase gas production (flatulence) and bloating. Individuals with gastrointestinal sensitivities such as irritable bowel syndrome should introduce these foods in small amounts to first assess tolerance. With continued use, tolerance may improve with fewer side effects.

If one does not have food sensitivities, it is important to gradually implement a high-fiber diet because a low-fiber diet may not only reduce the amount of beneficial microbiota, but increase the growth of pathogenic bacteria that thrive in a lower acidic environment.

Probiotic foods contain beneficial live microbiota that may further alter one’s microbiome. These include fermented foods like kefir, yogurt with live active cultures, pickled vegetables, tempeh, kombucha tea, kimchi, miso, and sauerkraut.

Future areas of research

The microbiome is a living dynamic environment where the relative abundance of species may fluctuate daily, weekly, and monthly depending on diet, medication, exercise, and a host of other environmental exposures. However, scientists are still in the early stages of understanding the microbiome’s broad role in health and the extent of problems that can occur from an interruption in the normal interactions between the microbiome and its host. [7]

Some current research topics:

- How the microbiome and their metabolites (substances produced by metabolism) influence human health and disease.

- What factors influence the framework and balance of one’s microbiome.

- The development of probiotics as a functional food and addressing regulatory issues.

Specific areas of interest:

- Factors that affect the microbiome of pregnant women, infants, and the pediatric population.

- Manipulating microbes to resist disease and respond better to treatments.

- Differences in the microbiome between healthy individuals and those with chronic disease such as diabetes, gastrointestinal diseases, obesity, cancers, and cardiovascular disease.

- Developing diagnostic biomarkers from the microbiome to identify diseases before they develop.

- Alteration of the microbiome through transplantation of microbes between individuals (e.g., fecal transplantation).

Related

- Ursell, L.K., et al. Defining the Human Microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2012 Aug; 70(Suppl 1): S38–S44.

- den Besten, Gijs., et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013 Sep; 54(9): 2325–2340.

- Morowitz, M.J., Carlisle, E., Alverdy, J.C. Contributions of Intestinal Bacteria to Nutrition and Metabolism in the Critically Ill. Surg Clin North Am. 2011 Aug; 91(4): 771–785.

- Arumugam, M., et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011 May 12;473(7346):174-80.

- Canny, G.O., McCormick, B.A. Bacteria in the Intestine, Helpful Residents or Enemies from Within. Infect and Immun. August 2008 vol. 76 no. 8, 3360-3373.

- Jandhyala, S.M. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Aug 7; 21(29): 8787–8803.

- Proctor, L.M. The Human Microbiome Project in 2011 and Beyond. Cell Host & Microbe. Volume 10, Issue 4, 20 October 2011, pp 287-91.

Terms of Use

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.

The Quadram Institute is looking to reduce the problems caused by microbes in the food chain by delivering an enhanced understanding of the ecology, evolution and survival strategies of pathogens in the food chain, including the drivers of antimicrobial resistance, to improve human health.

Microbes in the food chain represent a major global challenge to health and the economy, through foodborne infections and through their contribution to the problem of antimicrobial resistance.

Working in collaboration with other BBSRC-supported institutes, we are harnessing the latest genomic technologies to track the emergence, evolution and spread of foodborne pathogens in the food chain.

Our research focusses on E. coli, Salmonella, Listeria and Campylobacter, as the major causes of foodborne illness.

Our approach is to gather isolates from across the whole of the food chain, from soil, water, farms, animals, processing factories and humans, to get the fullest possible picture of the genomic epidemiology of these bacteria. Whilst many human isolates have been catalogued, comparatively few have been taken from the food chain environment, so completing this dataset will allow us to identify where foodborne pathogens arise from, and which are the major locations for bacterial communities that potentially could impact health.

Comparative genomics will allow us to identify what drives the emergence of antimicrobial resistance as well as other survival strategies, such as the formation of biofilms that resist cleaning, Salmonella’s ability to colonise plants and animals, and E. coli’s evasion of host defences.

Microbe Chain

The interdisciplinary team of researchers within the Quadram Institute is at the cutting edge of microbial cell biology, genomics, metagenomics, modelling and bioinformatics. Working strategically with partners on the Norwich Research Park and elsewhere, we will be developing novel approaches to sequencing and genomic analysis to better understand the microbiology of the food chain. This will allow us to identify new intervention strategies to stop pathogen spread in the food chain, either working through our ongoing collaborations with food production companies, or through novel techniques, potentially developed through bioprospecting for useful enzymes or probiotic bacterial strains.

Alison Mather

Epidemiology, genomics and antimicrobial resistance of bacteria

John Wain

Bacterial diversity and tropical infections

Microbe Food Chain

Justin O’Grady

Rapid infectious disease and foodborne pathogen diagnosis/detection

Mark Webber

Investigating the evolution of antimicrobial resistance

FOLIUM Science and Quadram Institute join forces in the fight against anti-microbial resistance

Researchers provide new insights into how antibiotic resistance develops

ViewGenomics helps understand COVID-19 in care homes

ViewBacteria Chain Of Infection

CLIMB Receives Honours in 2020 HPCwire Readers’ and Editors’ Choice Awards

ViewA bacterial virus helped the spread of a new Salmonella strain

Bacteria Chains

ViewMicrobe Chain

The Quadram Institute at the Norwich Science Festival

ViewWhole genome sequencing benefits for surveillance of bacteria behind gastroenteritis

View